You call me a cryptid. In the old tongue I was called nunnehi, commonly translated to mean “those who live forever.” I prefer the translation, “those who live anywhere.” Folks in Appalachia used to tell stories about me and my brethren to scare their children. “Don’t go out into the woods, or the snallygaster will get you!” “The wampus cat got another one of my chickens last night… left the entrails all over my front porch!” “Did you see those strange lights over the hills last night?” Nowadays, you might find me on a pin next to Mothman on someone’s bag, or in a poorly researched Tumblr post about how scary Appalachia is.

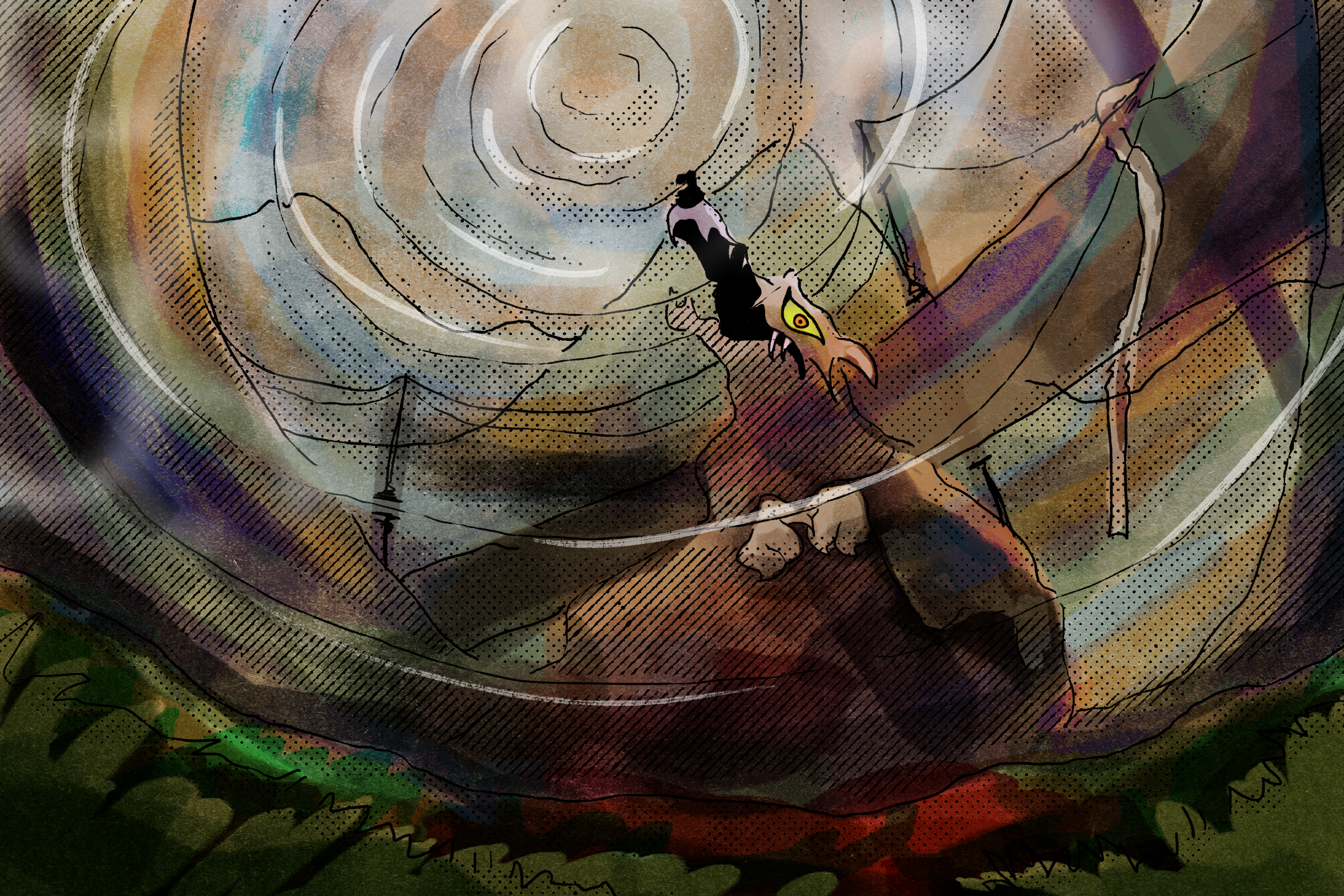

Those who know me know that I am not a monster. Sure, I might put on a scary face for tourists who spend too long in my woods after dark, so they don’t overstay their welcome, but I am not an evil spirit. I predate evil. I existed before these forests had names. I existed before there were forests. Before trees. Before plants with stems. Your lineage had only just figured out how to grow a backbone, and you were still writhing about as limbless fish beneath the seas, when my home, the Appalachian Mountains, burst from the collision of two long-forgotten continents. On that day, after eons of being trapped beneath the earth, beneath the waves, the mountains’ crests touched the sun, and so it has remained for the past 182,625,721,275 sunrises. A lot changed about the Appalachians over that many sunrises: rivers formed and faded, grand mountaintops softened into rolling hills, and many more than just I have found their home here, but nothing, neither hell nor high water, stood between the sky and the mountains. Until last month.

A fool builds his house on the sand, but the wise man builds his house on the rock. The rain descended, the streams rose, and the winds blew and beat upon that house, yet it did not fall, because it had its foundation on the rock. Storms ravage the coast, but they have always surrendered at the mighty fortifications of our mountains. But you warmed the earth and churned the great oceans, until they spat out this unholy squall. The rain descended, the floods rose, and the winds destroyed the fool and the wise man both.

You must understand that this was not my fault. It was not the fault of my people either. Where do you run when the high places have flooded? What do you do when you are given no warning? What do you do when the single lane road leading out of your town has been blasted off the map? Will you abandon those who cannot run—your animals, your children, your family? When you are on top of your roof, the very last high place, who do you cling to?

You won’t have to decide, because as you read this, you are dry and safe. I don’t despise you for that. Truly, I don’t. If you are from a place which has not yet felt the effects of climate change or a state with a blue legislative branch, I need you to recognize the blessings you have. You must reckon with your privilege. Faced with this suffering, you cannot let your cognitive dissonance turn to dismissive sneers. Sneers like:

“Well, why didn’t they just leave?”

“So glad I live in California and stuff like that doesn’t happen to us!”

“Hah, serves them right for voting for Trump.”

“It was just a bunch of climate-denying, racist hicks down there anyway.”

I don’t deny that Appalachia can be a cruel place. If you look, you’ll see it everywhere. A forest fire decimates an old growth forest. A wolf breathes its final breaths on a highway, with the treads of an 18-wheeler in its fur. A church hangs a Trump flag from its steeple. All of this is real. However, despite the ugliness, there is beauty. The sweetest blueberries grow from ash-ridden soil. Scientists cry tears of joy as five new wolf pups are born. An artist in Asheville decorates her studio with rainbows, honoring those she lost with her art. A church says all are welcome and means it, as they let those who no longer have homes sleep in their pews. You think the hurricane “served them right?” You’d damn the wretched and the redeemed?

I can tell exactly who doesn’t understand this nuance. The depravity of your soul leaks from your eyes. You reek of it, and the worst part is you will never have any idea just how much you stink. You call my people Appal-aye-shins instead of Appa-latch-ians. How fortuitous that the way you say a word tells me everything I need to know about you. You’ll complain that the AirBnB in Asheville won’t give you a refund. You’re the type to say you love hiking, but you just drive to the top of the mountain to take pictures in front of the parking lot. You say you like folk, but you mean Hozier, not bluegrass. You don’t know what a mandolin is. You’ll revel in your virtuous Instagram infographics, but you don’t even know your neighbor’s name. When someone asks what you love about your home, you’ll probably say godforsaken In-N-Out, because you have not reckoned with what it means to be from somewhere. I am that which lives anywhere, and you are that which lives nowhere. If I happen upon you in the odd hours of the night, I will not have mercy. I will tear you limb from limb, that much is for sure, but first I’ll drop you in the Catawba so that you can know what it feels like to have your lungs fill with swollen, angry, turbid water.

It matters not, in the end. My home is sunken, but yours will be ash soon. May you mourn for Asheville. May you mourn for Chimney Rock. May you mourn for Boone. And when the fires come for your home, may someone do the same for you.